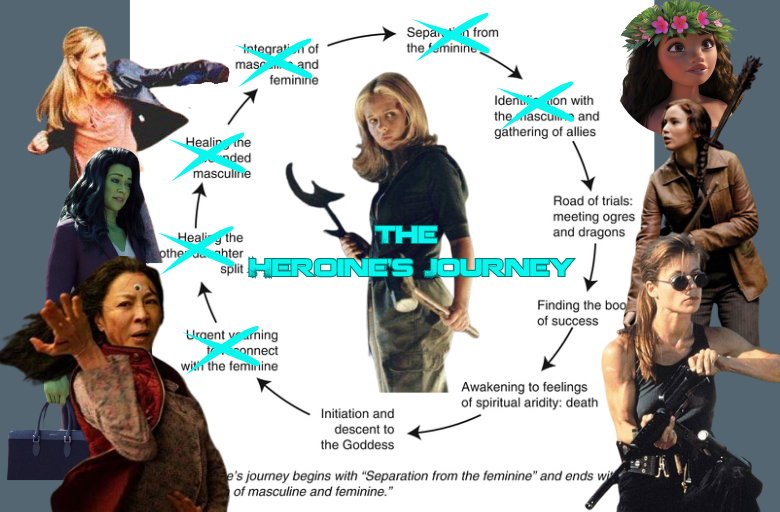

When people talk about the Heroine Archetype, Maureen Murdock’s The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness (1990) inevitably comes up – often treated like the gospel counterpart to Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces, (1949). And look, Murdock contributed something valuable to the conversation. She carved out space for the inner lives of women in myth and modern storytelling, which was missing from Campbell’s original Hero’s Journey diagram.

Her framework is also limited. Constricting. And honestly? It doesn’t fully reflect the kinds of heroines we’re writing, or desperately need, today.

Let’s get into it.

1. The “Internal = Feminine” / “External = Masculine” Split Doesn’t Hold Up

Murdock suggests the Heroine’s journey is primarily internal, while the Hero’s is external. Cue my eye twitch.

Characters are not IKEA bookshelves — you can’t just label one “outside stuff” and the other “inside stuff.”

Modern heroines (and all good protagonists) need journeys that are deeply internal AND deeply external. They fight monsters and inner demons. They rescue others and discover themselves along the way. The idea that heroines only grow emotionally while heroes get to blow things up feels like an ancient narrative.

Evelyn from Everything Everywhere? She’s punching multiversal security guards and unpacking generational trauma, sometimes in the same scene.

Sarah Connor? Internal breakdown, external survival.

Buffy? Kills vampires + wrestles existential despair.

The Heroine is not the “internal version of the Hero.” She’s both — because real complexity requires it.

2. The “Rejection of the Feminine” Doesn’t Map Onto Most Modern Heroines

One of Murdock’s central claims is that heroines start their journey by rejecting the feminine – distancing themselves from “feminine values” to succeed in a patriarchal world.

Sure, that shows up in some stories.

But making it the archetype’s defining move? That’s too narrow.

Characters like Buffy, Evelyn, Sarah Connor, Katniss, Moana — none of them reject femininity. They reject limitation. They reject expectations. They reject systems that tell them who they’re allowed to be.

Their struggles aren’t about “feminine vs masculine.”

They’re about identity vs pressure.

They don’t suppress their feminine side — they just don’t let gender dictate the parameters of their mission.

Murdock’s interpretation risks shrinking the heroine by making her entire journey about patriarchy’s impact on her psyche, instead of her own agency, conflict, and choices.

3. The “Search for the Father” Isn’t Universal – Sometimes It’s Just Family

Another Murdock staple: The heroine seeks the approval of the father or father figure. And sure — sometimes! But often what’s happening is not a psychological “search for the father” at all.

It’s simply family dynamics, full stop.

Evelyn’s relationship with her father isn’t about patriarchal validation. It’s about shame, migration, generational survival, and the role of love in reinvention.

Sarah Connor?

Her arc is about protecting a child who doesn’t even exist yet. She’s not chasing a father figure; she’s becoming one — or rather, transcending the need for one.

The problem is: Label every inter-generational story a “father quest” and suddenly you’re flattening genuine cultural nuance, trauma, and identity into Psych-theory Barbie.

Heroines deserve more complexity than that.

4. The Heroine Isn’t a Reaction to the Hero – She’s a Full Archetype in Her Own Right

Murdock defines the Heroine’s Journey largely as a counterpoint or corrective to Campbell’s. But defining women’s stories only in relation to men’s stories is the opposite of liberation.

The Heroine Archetype isn’t a derivative. She’s not an add-on to the Hero package.

She has her own motivators:

- Protection

- Belonging

- Connection

- Meaning

- Transformation

- Love

- Legacy

And her own style of courage:

- Emotional insight

- Empathy as strategy

- Identity as battleground

- Care as radical act

- Resilience forged in quiet places

Her power isn’t defined by gender — it’s defined by humanity under pressure.

5. The Binary Model Just Doesn’t Fit Our Storytelling Landscape Anymore

Murdock’s work is steeped in 1980s feminist psychology — useful, but dated.

Today’s heroines exist in a storytelling ecosystem shaped by intersectionality, trauma theory, diaspora narratives, identity politics, multiversal storytelling, and genre-blending.

Heroines today aren’t wrestling with “the feminine” or “the masculine.”

They’re wrestling with:

- Identity

- Cultural expectation

- Generational inheritance

- Autonomy

- Meaning

- Love

- Survival

- Connection

The battleground isn’t gender. It’s belonging. And that requires a far more fluid, adaptive model than Murdock offered.

So What Is the Heroine’s Journey, Then?

If we need to have a female version of the Hero’s Journey (debatable), then The Heroine’s Journey can not be a rejection of the feminine.

It’s not a search for the father.

It’s not an internalised version of the Hero’s Journey.

In my mind, The Heroine’s Journey is this:

A character who saves the world by learning how to save herself –

and then uses that self-knowledge to heal, protect, and transform others.

Her power isn’t louder than the Hero’s. It’s just different:

- More relational

- More empathetic

- More psychologically complex

- More focused on integration than domination

- More willing to change and be changed

Her victories aren’t measured in bodies, but in bonds.

Publications and productions referenced in this blog post:

Murdock, Maureen. The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness. New York, Shambala Publications (1990).

Campbell, Joseph. Hero with a Thousand Faces. USA, Pantheon Books. (1949).

Buffy The Vampire Slayer. Created by Joss Whedon, produced by Mutant Enemy Productions, Sandollar Television, Kuzui Enterprises, 20th Century Fox Television (1997 – 2003)

Everything Everywhere All at Once. Directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert. Produced by A24, Gozie AGBO, Ley Line Entertainment, Year of the Rat, IAC Films, (2022)

Hunger Games. Adapted for film by Nina Jacobsen, directed by Gary Ross produced by Color Force. (2012).

Terminator. Written by James Cameron and Gale Anne Hurd, directed by James Cameron. Produced by Gale Anne Hurd, Hemdale, Pacific Western Productions Euro Film Funding. (1984)

Moana. Directed by John Musker and Ron Clements, produced by Osnat Shurer, production company Walt Disney Entertainment Studios. (2016)